(Pictures are of deconstructivist architecture)

“There is in deconstruction, a self-explanatory figure which imposes its necessity in accumulating the forces trying to repress it”-Jacques Derrida

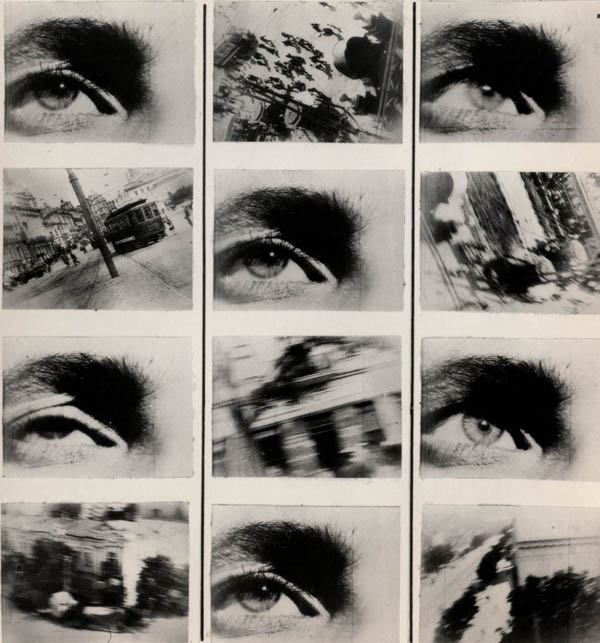

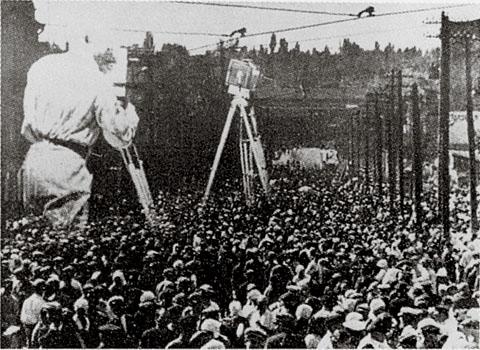

Derrida questioned the ideals of structuralism, claiming that they were chasing a myth, their goal being to expose or find an ideal, true underlying structure. In fact, Derrida considered any and all desire for truth and meaning in art, writing, or life, ‘logocentric’ (refers to the western take on getting to the core; center of things). Derrida believed most things were an illusion and that relationships between objects and people were too complex to be so simply deciphered. For Derrida, there are two feasible approaches to analyzing a text. One is ‘naive’ and the other ‘deconstructionist’. He believed straight-forward thinking and consistent meanings in literature or art were ludicrous.

-----------

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I often find myself thinking about how everything is so haphazard outside of our systematic worlds. How we have no control over anything, except a fragment of our lives that none of us even have considerable control over. There are infinite ways to look at a piece of art. What the viewer thinks may depend on what they think of the artist, or not. Whether they had a bad day or it rained (or not!). Maybe the meaning they found was purely dependent on them hitting the snooze button this morning. How could any conclusion anyone makes about anything be correct, if their ‘true’ thoughts on something depends on petty or unknown factors? We cannot choose the influences in our daily lives, and for all we know, they might cause us to find certain meanings in things, or think different thoughts. And so we all live in our little realms, but no one can be more correct than another, since there is no independent universal standard by which we can compare our literature or art to. Instead, we all have our momentary, personal ‘truths’. Who’s to say these are not illusions, as what standard supports their supposed truth? Can they not be as true as they are false?

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I often find myself thinking about how everything is so haphazard outside of our systematic worlds. How we have no control over anything, except a fragment of our lives that none of us even have considerable control over. There are infinite ways to look at a piece of art. What the viewer thinks may depend on what they think of the artist, or not. Whether they had a bad day or it rained (or not!). Maybe the meaning they found was purely dependent on them hitting the snooze button this morning. How could any conclusion anyone makes about anything be correct, if their ‘true’ thoughts on something depends on petty or unknown factors? We cannot choose the influences in our daily lives, and for all we know, they might cause us to find certain meanings in things, or think different thoughts. And so we all live in our little realms, but no one can be more correct than another, since there is no independent universal standard by which we can compare our literature or art to. Instead, we all have our momentary, personal ‘truths’. Who’s to say these are not illusions, as what standard supports their supposed truth? Can they not be as true as they are false?